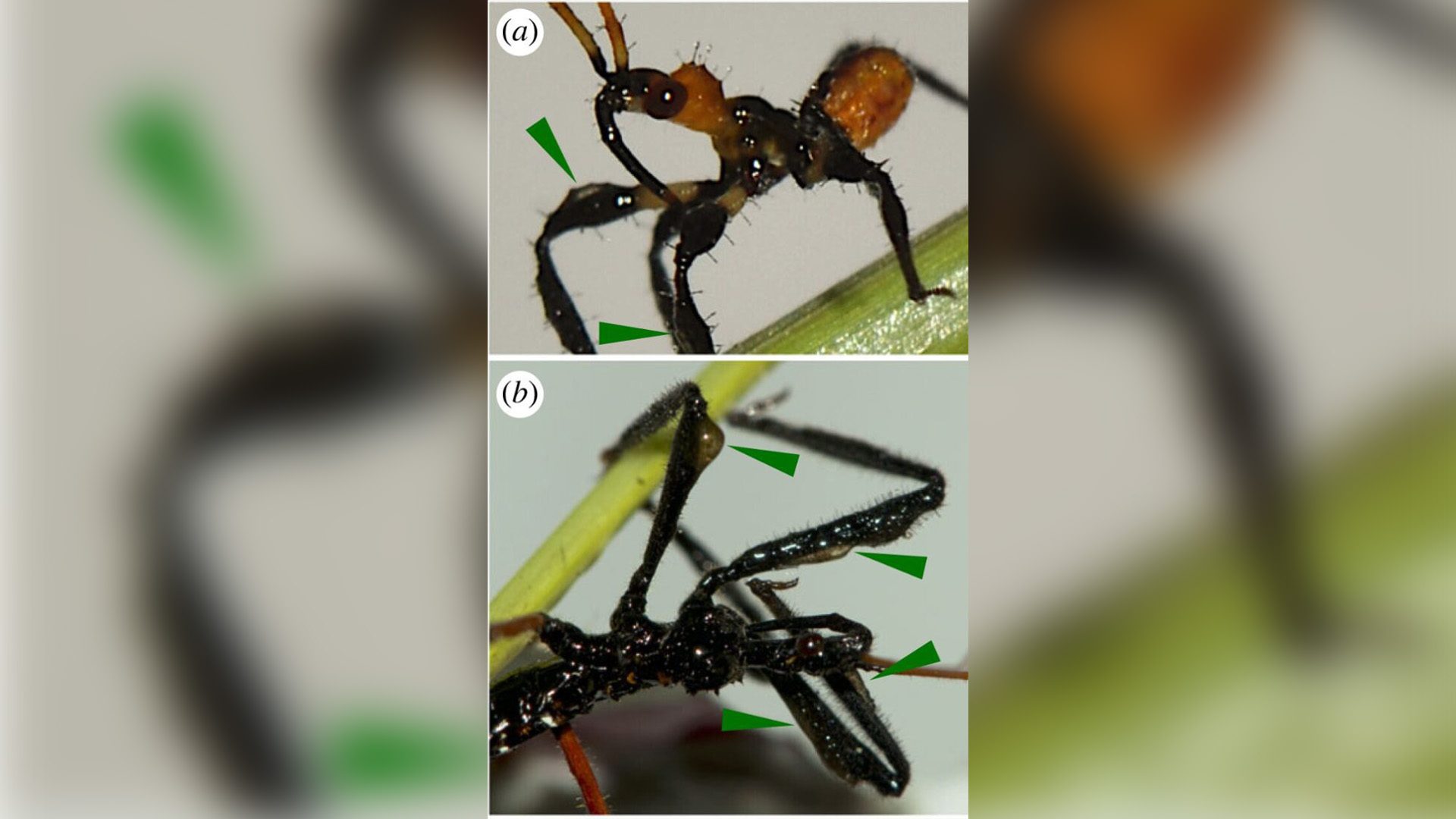

Recent research shows that assassin bugs in Australia are utilizing resin from spinifex grass to ensnare their food. The creatures slather themselves in the gluey gum to help them both catch and keep their prey.

Although this is rare in nature, there are certain insects that employ tools. Ants, for example, use particles to build bridges and beetle babies use poop as a deterrent to parasites. The rareness of this behavior is due to its inherent complexity.

Tool-use requires both an appropriate choice of environmental item and adequate manipulation in order to achieve a beneficial outcome. Though most tool-using animals are vertebrates (mammals and birds), some invertebrates such as assassin bugs are part of this select group of animals.

The term “assassin bug” groups a variety of insects that are united in the gruesome way they kill their prey, typically by piercing the prey with its proboscis and pumping digestive enzymes inside the parasite to kill it. The authors of the recent study have stated that the new discovery makes assassin bugs “a particularly promising case for understanding the ecological and behavioral conditions that facilitated the otherwise unlikely evolution of tool-use.”

Macquarie University biologists Marie Herberstein and Fernando Soley observed 125 Australian assassin bugs from Western Australia’s Kimberly region in wild conditions and in a nearby makeshift lab in a tent. Australian assassin bugs can be commonly spotted perched on Triodia stems (a native tussocks grass commonly referred to as spinifex) which is found in the dry regions of Australia and produces a sticky resin.

“Assassin bugs manipulated an environmental item (the resin), by taking it out of its usual context and applying it onto their bodies,” researchers write in the study, “Thus gaining a selective advantage through improved prey capture.”

Soley and Herbstien predicted that, if the resin is used as a tool, the bugs using the resin will be better at catching prey. They initially took 26 assassin bugs found near or on curly spinifex (Triodia bitextura) back to their tent laboratory for further observation.

The research team placed the insects in a glass jar with a stick and introduced two types of prey: flies and ants. They also used makeup removal pads to gently wipe the resin off of the insects’ bodies, to compare the success rate. The team discovered that the resin-covered bugs were 26 percent more successful at capturing both types of prey compared to those not employing the resin as a tool. The flies were the most difficult for the bugs to catch, with roughly 64 percent of the flies in the assassin bug group without the resin escaping capture.

“Prey never appeared to be fully stuck to the resinous surface of the assassin bugs,” Soley and Herberstein explain. “Rather, it appears that brief, temporary adhesion, delayed prey responses sufficiently enough for the assassin bugs to grasp and stab their prey”.

Scientists had previously theorized that assassin bugs would improve their hunting abilities if coated in the sticky resin of plants, but this had never been tested in experiments previously. Both in the lab and in the wild, the researchers observed the bugs scraping resin off of the spinifex leaves and meticulously applying it to their bodies (particularly their front legs). Even newly hatched and isolated nymphs were coating themselves in the resin, suggesting the behavior is ingrained in the species of insects.