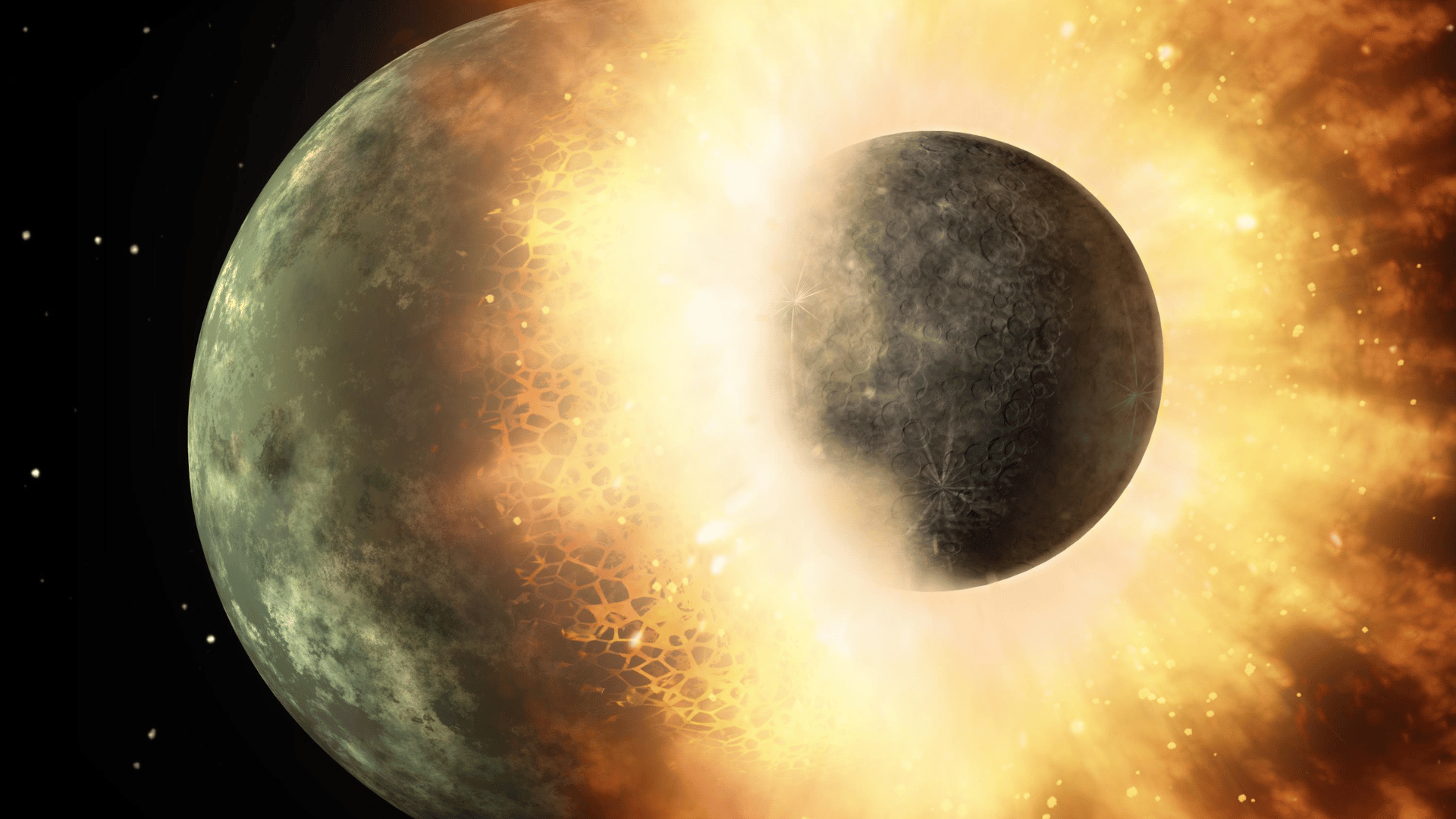

Scientists may have discovered remnants of an ancient planet that they believe smashed into Earth as it was forming billions of years ago, resulting in the creation of the moon.

The theory is called the giant-impact hypothesis, but what happened to the ancient planet called Theia remains a mystery. No evidence of the planet has been found in our solar system and many researchers assumed that any debris Theia left on Earth blended into the planet’s interior.

A new theory, however, suggests that remnants of Theia remain partially intact and buried beneath the Earth. It’s possible that molten slabs of the planet could have embedded themselves within Earth’s mantle after impact and before solidifying, leaving portions of the planet’s material resting above Earth’s core approximately 1,800 miles beneath the surface.

Geophysicists were already aware of two large and distinct masses embedded deep within the Earth. First detected in the 1980s, the large low-velocity provinces (LLVPs) lie beneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean.

Dr. Qian Yuan, a geophysicist and postdoctoral fellow at the California Institute of Technology and the new study’s lead author, gained a new understanding of the LLVPs when he attended a 2019 seminar at Arizona State University that outlined the giant-impact hypothesis.

He learned about the details of Theia and, already knowing of the mysterious masses as a geophysicist, he began to wonder if the two were connected. He began perusing scientific studies and he realized that no scientist had yet proposed that LLVPs might be fragments of Theia.

“I was afraid of turning to other people because I (was) afraid others would think I’m too crazy,” Yuan said.

When he originally proposed this idea in a paper in 2021, it was rejected three times. Then he came across scientists who did the type of research he needed.

Their work suggested that the planet’s collision likely didn’t entirely melt into the Earth’s mantle, allowing the remnants to cool and form solid structures.

“Earth’s mantle is rocky, but it isn’t like solid rock,” said Dr. Steve Desch, a study co-author and professor of astrophysics at Arizona State’s School of Earth and Space Exploration. “It’s this high-pressure magma that’s kind of gooey and has the viscosity of peanut butter, and it’s basically sitting on a very hot stove.”

The researchers then had to ask whether the density of the material left behind by Theia could match the density of the LLVPs. To answer this, researchers sought high-definition modeling with 100 to 1,000 times more resolution than their previous attempts.

The models showed that, if Theia were a certain size and consistence and struck the Earth at a specific speed, it could leave behind massive chunks similar to the LLVPs within the Earth’s mantle.

The study Yuan recently published includes coauthors from a variety of disciplines across a range of institutions, including Arizona State, Caltech, the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, and NASA’s Ames Research Center. Though the theory is still a hypothesis, this new research makes a compelling case and will allow scientists to conduct further research in the future.

“That was very, very, so very exciting,” Yuan said. “That (modeling) hadn’t been done before.”