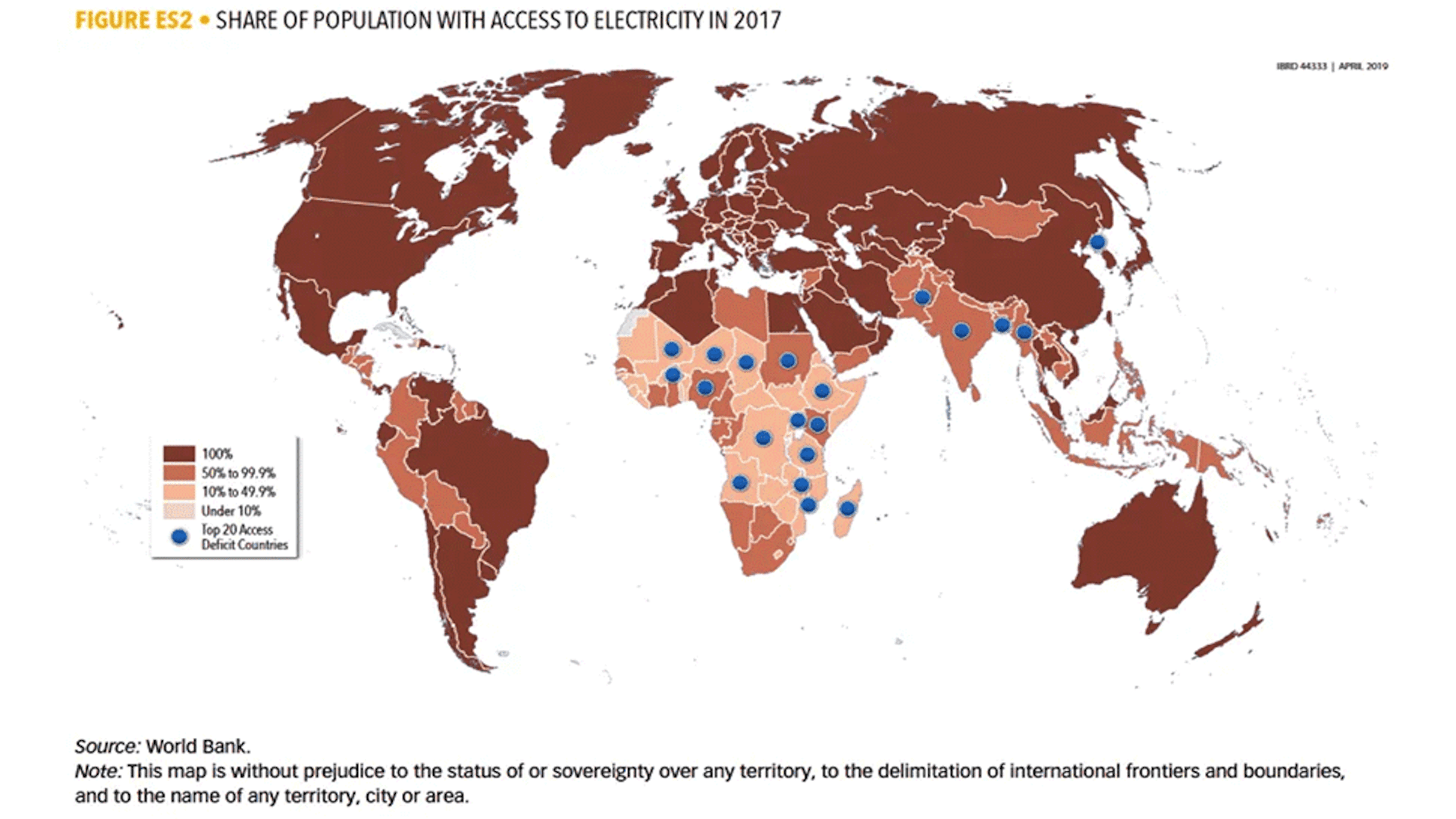

The definition of energy poverty is the lack of access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy. As of 2021, more than 750 million people have no access to electricity, and over 3 billion people rely on wood, coal, charcoal, and animal waste for cooking and heating.

To find out more about the worldwide issue of energy poverty and what can be done to decrease the number of people who do not have adequate energy, we talked to Zainub Dungarwalla, a Partner at Helixos and Chair of the Nuclear Futures Committee at the U.S. Department of Energy. Zainub is working to position the U.S. energy system for a sustainable future through engagement with utilities and the Gateway for Accelerated Innovation in Nuclear (GAIN). Her new work at Helixos is focused on helping others around the world understand the different energy and sustainability futures that may emerge.

Tomorrow’s World Today (TWT): Who and where is most impacted by lack of access to energy?

Zainub Dungarwalla (ZD): In populations that are difficult to reach, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, many do not have access to electricity. The United Nations estimates that 1 in every 2 people in this region lacks access. However, it’s also important to remember that while there is a lot more access in the US, it is not affordable for many. This is why many regions have safety nets in place to keep heating/cooling on when weather extremes take over. In these situations, keep in mind that the lower the income of a family, the greater percentage of their paycheck goes towards paying their utility bill. For many struggling families, this means having to decide between putting food on the table, paying medical expenses, or keeping the lights on. Unfortunately, these issues are often interconnected as poverty also creates significant health and education disparities. Just consider how difficult it is for a child to complete their homework if sitting in darkness.

TWT: How can nuclear energy prepare us for a changing landscape? How can energy experts, scientists, and communicators help the public make sense of these changes? Is that the role of those experts?

ZD: In many of the regions with energy poverty, remote areas struggle the most and need off-grid solutions such as microgrids that can be powered by a blend of renewables and micro nuclear reactors. In inner-city regions, where population densities continue to rapidly increase, nuclear reactors that provide big power with small physical footprints could be key to enabling reliable, clean grids—as well as the creation of affordable clean hydrogen for heavy-duty vehicles, drinkable water for communities, carbon-free sourced ammonia for the coffee industry, and deep decarbonization of big industrial processes like cement production.

The energy landscape has never been more complex and uncertain than it is today. Everyone involved—from energy experts, scientists, and communicators—must understand that we need to evolve our work from looking solely at technology and economics, to including changing societal values, environmental concerns, and future-facing policies. This means also changing the way we all speak to the public to enable better understanding and the formation of a shared vision for the future.

TWT: What role does nuclear play in ensuring equitable access to energy to end energy poverty?

ZD: Across the globe, many of us are trying to figure out how we can decarbonize faster without making electricity prices soar out of reach for families. Several studies have been released that show adding nuclear power to the energy mix can greatly limit the cost involved in reaching 100% clean energy goals, from an EnergyNorthwest E3 study, Stanford University study of California, to a Princeton study looking across the whole of the U.S. The Princeton study, in particular, found that an energy mix that allowed for nuclear power provided the lowest transition cost, top health benefit, required the least amount of added pipes/wires, and had the least land use. This is important to highlight because any funds saved on our net-zero pathways can be repurposed to help our communities in other ways, from better school funding to increased aid for social services.

TWT: What is scenario planning? What is its value? How can it help us into the future?

ZD: A number of years ago, I was asked to think through strategies to best position the largest nuclear plant in the US for the near- and long-term future. I did what any other good engineer would do when faced with a big task—I started reading. As I opened more and more tabs on my computer, spanning economic studies, news articles, and electricity models, I had this growing feeling that I needed to find a better way to move from processing this information to forming a good strategy before my computer crashed.

It was around this time that I happened to be in the right place at the right time—right outside an elevator. A co-worker from another group introduced me to an external consultant as they were getting off this elevator. This consultant, Dr. Cynthia Selin, introduced herself and described her expertise as helping others form business strategies in markets with growing complexity and uncertainty. I was both intrigued and a skeptic.

Over the months that followed, I was fortunate enough to engage in the scenario planning work and I had an endless list of questions along the way. What I quickly realized was that this process was invaluable because it made us admit that we did not have a crystal ball and cannot, no matter how much math and modeling we throw at it, predict the future with any kind of certainty more than a few years out.

We realized we had to shift from assessing the future based on forecasts alone (probability) to a position of curiosity regarding what could happen in the future (plausibility). Allowing for a consideration of what is possible widened our view of the changing world and helped us go beyond straight-line future projections. It also made us have a deeper appreciation of societal, environmental, and political drivers of change, as we had been defaulting to focusing on technology and economics alone like many in the utility industry. This exercise in strategic foresight is worthwhile as it can also reveal new opportunities that an industry can be proactive about pursuing. In some instances, it is possible to transform a perceived threat into an opportunity.

TWT: What are the main external factors that will shape the future of nuclear power in 2040? How does scenario planning help predict this?

ZD: Consider just ten years ago that no one in the nuclear industry was talking about hydrogen production. It didn’t come up in conversation, nor was it built into any utility forecasting model. It was a weak trend that has built up tremendous momentum over the last few years. Those who were able to act quickly and leverage this opportunity to date were those keeping a keen eye on the world in which they operate.

The power in this scenario planning methodology is that you realize you can’t answer with any certainty what the main external factors will be that shape the future of nuclear power in 2040, 2050, or even 2100. What you can do, however, is continuously dedicate effort to scanning the contextual world in which nuclear power exists to check and adjust assumptions, understanding, and strategies along the way because known trends today will continue to fold into unknown trends of the future. In the words of Joseph Fuller, Professor of management practice, Harvard Business School, “it’s the assumptions that kill you, not your competitors.”

Ultimately, scenario planning is how good business strategy is formed across many Fortune 500 companies, and this is why the Oxford scenario planning method is the best tool for helping us all navigate our plausible energy futures together, including working to end energy poverty.

(Ramírez R and C Selin. 2014. “Plausibility and probability in scenario planning.” foresight, 16(1): 54 – 74.)

Read more about nuclear energy HERE, or stream Tomorrow’s World Today’s four-part exploration of nuclear energy on SCIGo and Discovery GO!