Researchers recently used portable chemical imaging technology to discover hidden details in ancient Egyptian paintings. A new study published in open journal PLOS One focuses on two paintings from the Theban Necropolis near the Nile River. The paintings date back more than 3,000 years, and the new study displays how researchers can use advanced technology to study ancient sites.

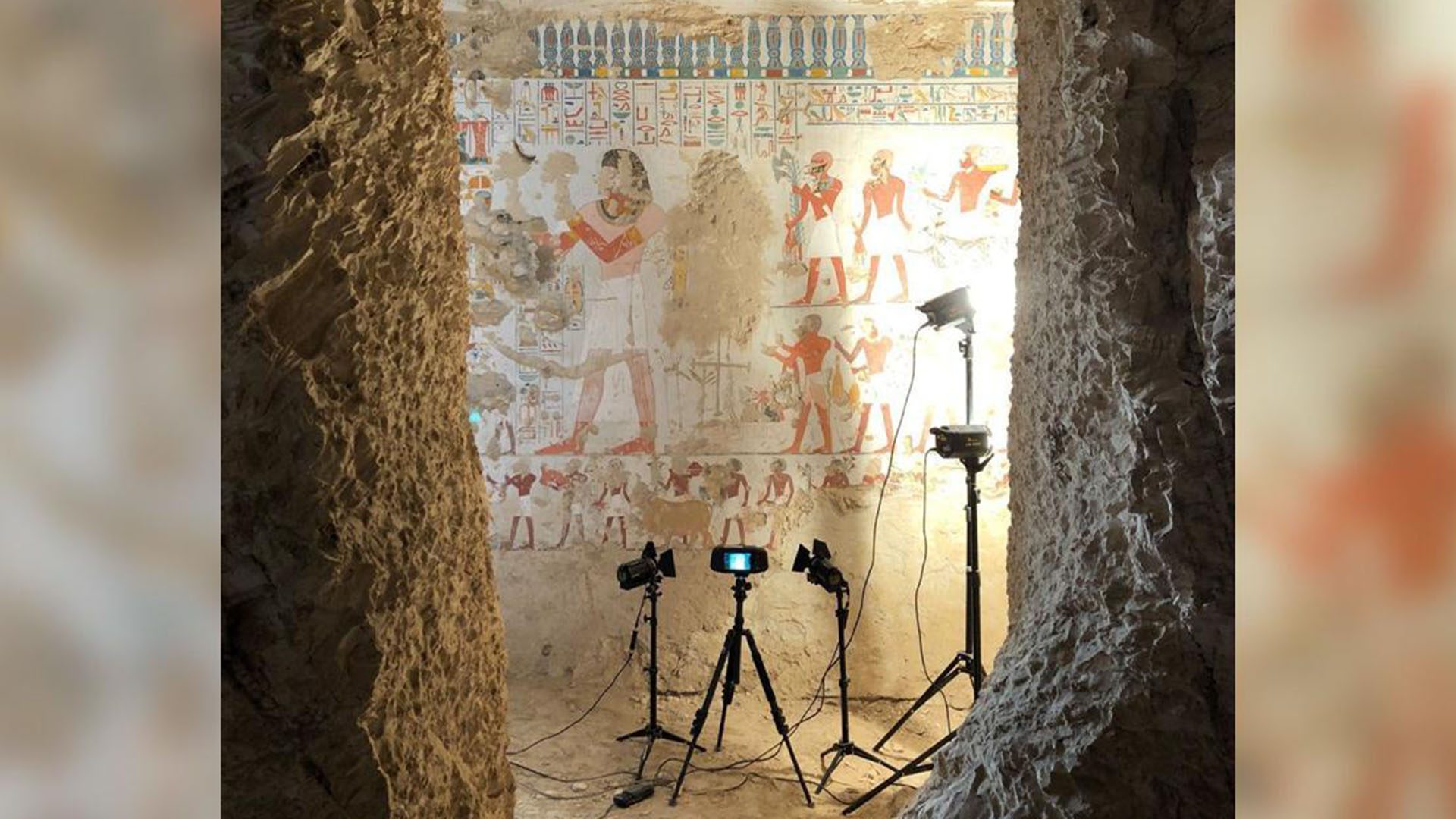

The x-ray fluorescence imaging process allows the researchers to analyze the chemical composition of the paint and how it way layered, providing a new look at the techniques that each artist used to make the works. The new study also marks a shift in traditional Egyptology as the analysis was performed with advanced portable devices, whereas most studies are traditionally performed in laboratories or museums.

Chemical imaging technology involves X-ray fluorescence. X-rays create a map of the surface of the painting down to a molecular level, including its chemical properties. Another process, hyperspectral imaging, analyzes the works on multiple wavelengths including ultraviolet or infrared.

“What is new is the way we are trying to use those tools,” said Philippe Martinez, an Egyptologist at the Sorbonne University in Paris and lead author of the study published Wednesday in the journal PLOS One. “The way these works of art have been dealt with before has been mainly, purely analog, and they have been somewhat taken for granted — nobody has been really looking at them from the point of view of the artists. We want to understand how these paintings were made.”

Previous studies have formed theories regarding the workflow of artists during this period, which have found that ancient Egyptians rarely made alterations to paintings during the process or afterward. The team in this study selected works already known to have alterations in hopes of gaining some insights regarding reasons for the edits.

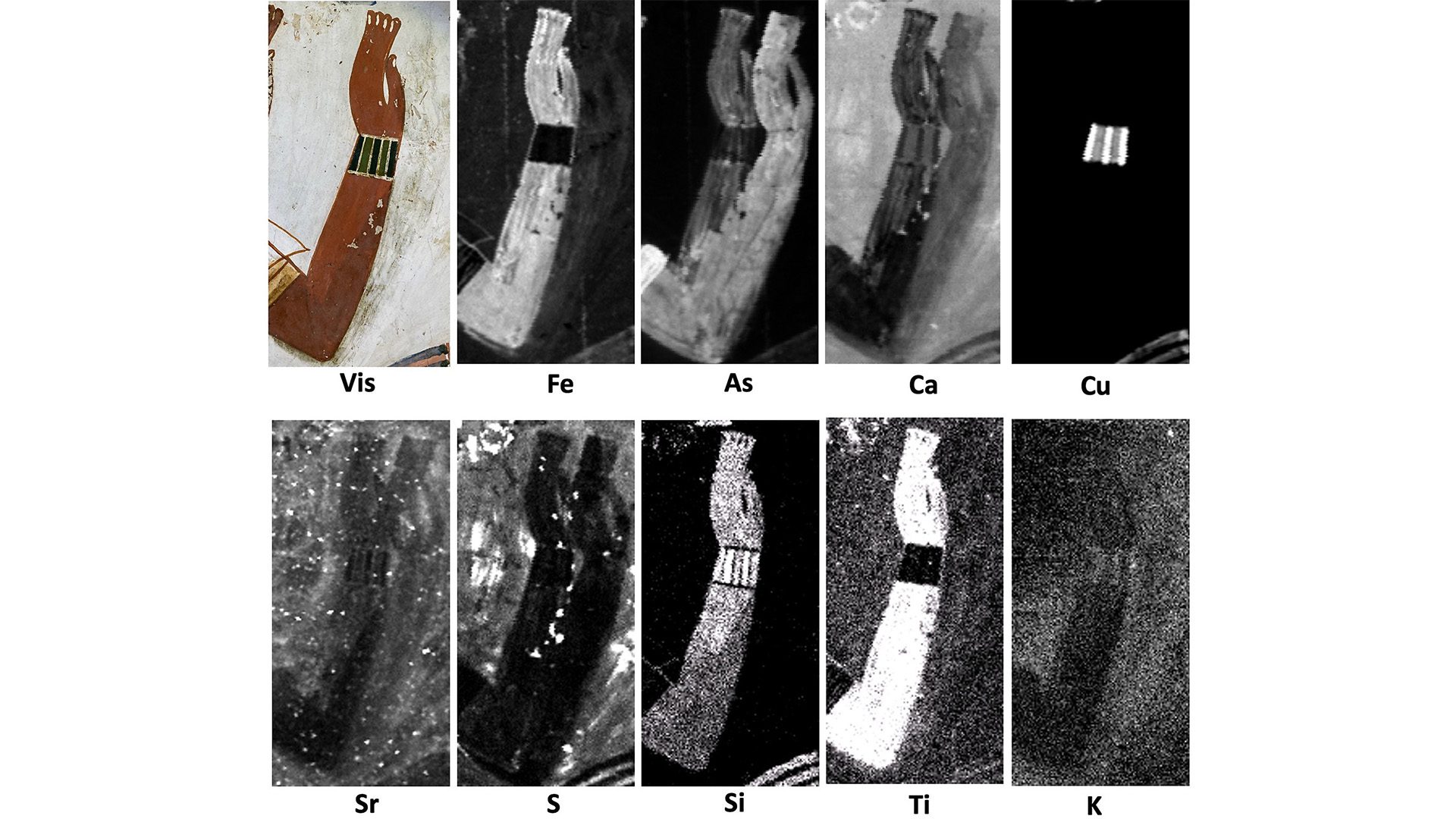

Prior research of ancient Egyptian art has focused on pigment samples taken offsite to labs for analysis, which researchers noted are generally in agreement with archaeological observations. Authors of the study noted that the pigments used by ancient Egyptians contain elements detectable with the new technology. For example, silicone, calcium, and copper are detectable with XRF imaging to find the color Egyptian Blue.

“Menna is a little bit like the Mona Lisa of Egypt,” Martinez said. “It’s one of the best tombs, known for 200 years, very well preserved.”

Researchers examined the alterations, including a hidden third arm in a scene in which the ancient Egyptian official Menna and his wife are pictured admiring Osiris. This alteration, however, has been known since the discovery of the painted tomb chapel of Menna in 1888 because it is visible to the naked eye.

“The interesting thing is that even if it was just seen as a mistake to be corrected, the way it is corrected differs very, very strongly from the original. Either the owner of the tomb, or the group of artists, or whoever was directing the process, saw this as something that was wrong, but it was corrected with materials and artistic means that show a completely different thought process.” Martinez stated.

During their examination of the portrait of Ramesses II, the team discovered various alterations to his crown, necklace, and other royal items. The team has speculated that these edits could be due to some change in the symbolic meaning of the artifacts over time.

“As an Egyptologist I’m trying to forget what I know, because the accumulated knowledge of the last 200 years is stopping us from seeing what is in front of us,” Martinez stated. “We have to relearn the Egyptian paintings and look at them in a new way, because the colors are now very different from what they used to be — hopefully the chemical analysis will help us to actually redefine them.”