The goal of sustainable agriculture is to meet society’s food needs in the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This looks different for every farmer and every company, but one thing is certain: practicing sustainable agriculture is necessary to ensure a viable food supply and environment for future generations.

And, with the global food demand projected to increase by 50 percent by 2050, sustainable agriculture is more important than ever. Here is the evolution of how sustainable agriculture came to be since the 1940s and what it looks like today.

The 1940s-1970s

The Green Revolution

Following World War II, a new problem emerged: feeding the world’s rapidly growing population. As early as 1946, President Harry S. Truman warned about a coming “famine of half the world.”

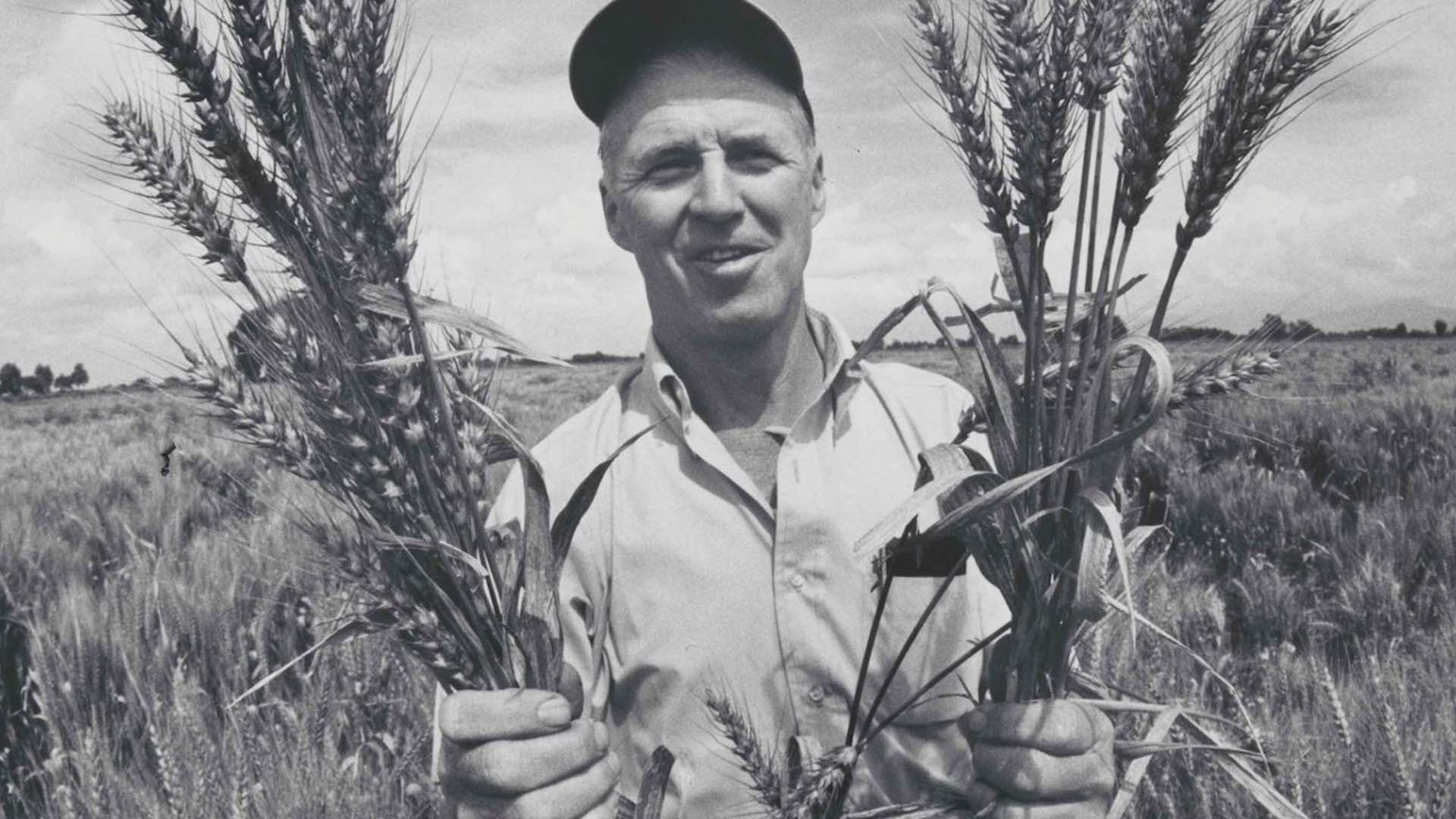

Before Truman’s statement, Norman Borlaug, an agricultural scientist, had already been working to solve this problem. He worked with the Mexican Agriculture Program (MAP), initiating practices in Mexico like selective breeding, fertilizing, hybrid crossing, and more to increase crop yield and get more grain per acre. By 1963, 95 percent of Mexico’s wheat crop came from Borlaug’s varieties, and the harvest was six times larger than when he arrived in 1944.

Following the crop success in Mexico, MAP and its practices turned to India, Pakistan, and the rest of the world, thus beginning the Green Revolution. As a result of the revolution, farmers increased their use of chemical fertilizers, insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides, adopted high-yielding crop varieties, and purchased machines for cultivating and harvesting their crops.

The Green Revolution was highly successful in reaching its goal to increase crop yield. For example, after applying Borlaug’s semi-dwarf varieties and practices, Pakistan’s wheat yields nearly doubled from 4.6 million tons in 1965 to 7.3 million tons in 1970. Borlaug even won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work across the world.

Sustainable Agriculture Movement Begins

While the Green Revolution was occurring, however, a growing movement emerged: the sustainable agriculture movement. For example, the Ontario-based group, The Land Fellowship, was established in the early 1950s to promote sustainable agriculture, and many academic studies were published on sustainable issues in the 1950s and 1960s. Both received little attention from the agricultural establishment and the general public, although there was a slow but steady increase in interest in the smaller farm community.

Other parts of the sustainable agriculture movement questioned some of Borlaug’s practices and their effect on the environment. Notably, geography professor Carl Sauer warned in the early 1940s that the Green Revolution’s plant reeding technique would result in negative effects on the country’s resources and culture.

In 1962, Rachel Carson’s book “Silent Spring” brought many agriculture issues to the forefront of popular culture and society, highlighting the effects of DDT and other pesticides on wildlife, the natural environment, and humans. Carson called for humans to act more responsibly towards the earth and brought up concerns about the long-term effects of agricultural chemicals on the ecology.

The 1970s-1990s

Increased Policies

In the 1970s, consumers and government began to become more environmentally aware, increasingly fueling the sustainable agriculture movement and organic farming. For example, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was formed in 1970; in 1972, the organization issued a cancellation order for DDT based on its adverse environmental effects.

By the 1980s, U.S. lawmakers increasingly responded to funding research initiatives regarding sustainable agriculture, such as the 1985 Food Security Act. However, this act and others, like the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973, introduced target prices and deficiency payments, promoting commodity crops by lowering interest rates. These policies incentivized profit over sustainability by benefiting farms that maximize their production output. This also meant that more commodity crops like corn, wheat, and cotton were grown, reducing biodiversity.

Further, in 1989, $4.45 million was allocated for the SARE, the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program. Congress authorized SARE in 1990 with Subtitle B of Title XVI of the Food, Agriculture, Conservation, and Trade Act of 1990.

In this act, Congress defined sustainable agriculture as an integrated system of plant and animal production practices having a site-specific application that will over the long-term:

- satisfy human food and fiber needs;

- enhance environmental quality and the natural resource base upon which the agriculture economy depends;

- make the most efficient use of nonrenewable resources and on-farm resources and integrate, where appropriate, natural biological cycles and controls;

- sustain the economic viability of farm operations; and

- enhance the quality of life for farmers and society as a whole.

Increased Criticism

The ’70s and ’80s also saw an increase in criticism about the Green Revolution. Environmentalists dissented over the widespread use of synthetic fertilizers, increased irrigation needed for its practices, and the resulting lack of biodiversity that occurred as it relied on just a few high-yield varieties of each crop.

In response to the dissenters, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) was founded in 1971 to funnel money to Green Revolution research. Additionally, money was sent to seed varieties to farmers around the world to further increase yields with the hope to help farmers and developing nations breed resistance to diseases and pests and to market their produce.

By the early 1980s, CGIAR continued to emphasize food production with the new qualification that this production should be sustainable, adding improved nutrition and the wellbeing of the poor to the agenda.

Towards the end of the 20th century, more governments found it difficult to continue to subsidize irrigation projects or to supply cheap fertilizers. Many critics argued that CGIAR’s concentration on only a few staple crops supported by modern chemicals and irrigation forced out farmers of indigenous crops, aligning with the early critique of the Green Revolution.

In response, CGIAR broadened its research activities and began projects to help small, poor farmers market their crops better and feed their local populations. In the 1990s, CGIAR also began pushing sustainable food security, sustainable agriculture, improved climate resilience, and secure livelihoods.

Sustainable Agriculture Today & The Future

Regenerative Agriculture

From the 2000s to today, the public is more aware of how pesticide-contaminated farm runoff pollutes fresh-water resources, while nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers can poison the oceans. Additionally, conventional farming has been heavily criticized for causing biodiversity loss, soil erosion, deforestation, and more.

One sustainable agricultural practice that has picked up steam is regenerative agriculture. In the 1980s, Robert Rodale of the Rodale Institute coined the term “regenerative agriculture” to distinguish a kind of farming that goes beyond sustainable. The institute formed the Regenerative Agriculture Association which began publishing books about the topic in 1987.

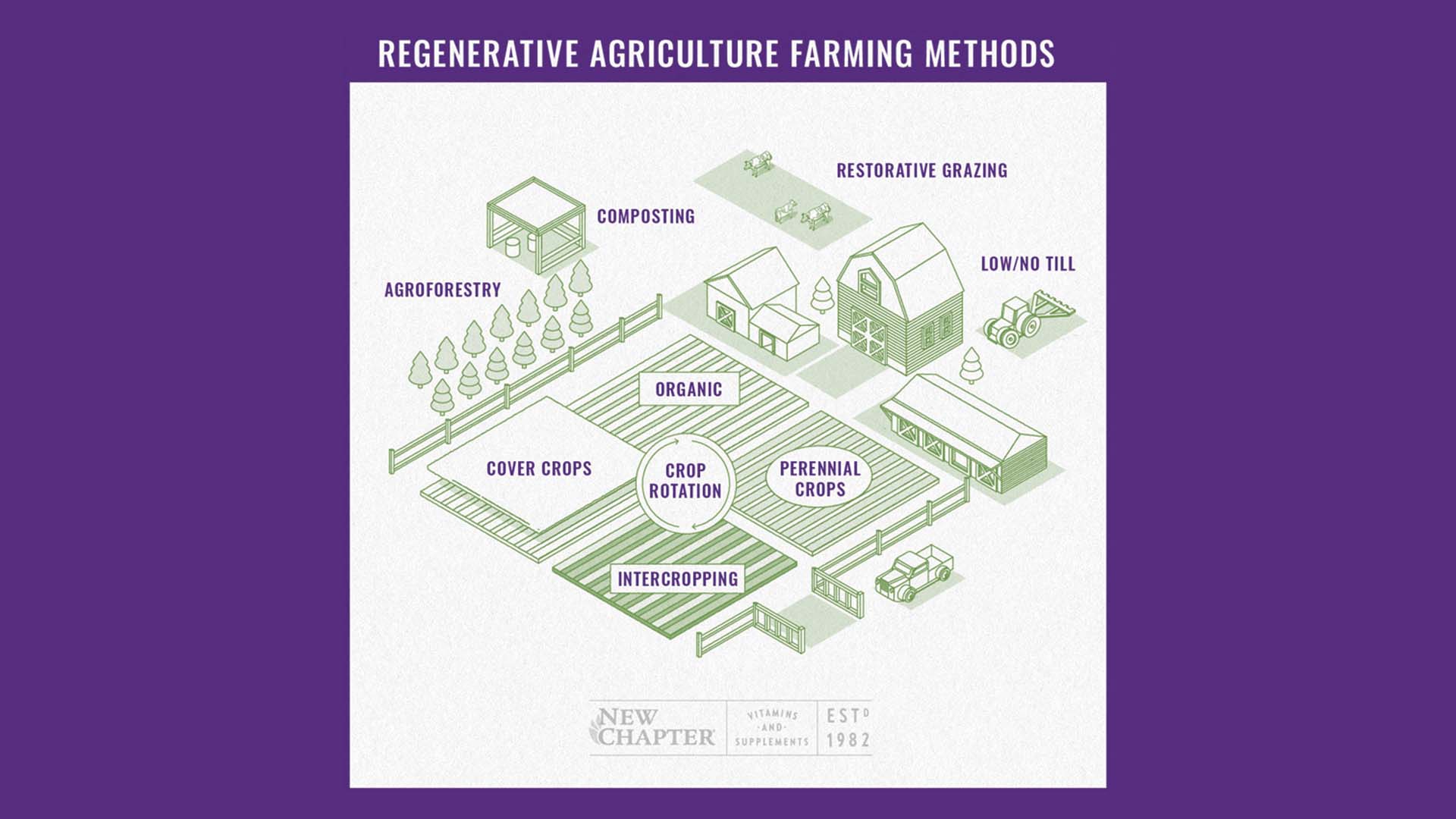

Unlike conventional agriculture, regenerative agriculture does not use fertilizers, pesticides, or genetically modified organisms (GMOs); instead, it is a combination of sustainable agriculture techniques that sequester carbon in the soil while improving soil health, crop yields, water resilience, and nutrient density. And, unlike organic agriculture, it incorporates management principles focused on the soil and the health of the land, which includes the soil, water, plants, animals, and humans. Organic production does not try to rebuild or regenerate the soil.

Many major companies have recently announced taking part in regenerative agriculture as a part of their sustainability plan. For example, in 2021, PepsiCo announced it was adopting regenerative agriculture practices on 7 million acres of farmland, Cargill committed to 10 million acres by 2030, and Walmart has pledged to 50 million acres by 2030.

Practices

There are many current and future sustainable agriculture practices that many companies and farms implement today. For example, rotating crops, planting cover crops and perennials, reducing or eliminating tillage, integrating livestock and crops, applying integrated pest management, and adopting agroforestry practices, to name a few.

Additionally, many innovative products come each year that promote sustainable agriculture. In 2022, OnePointOne builds a vertical plane aeroponics farming space that uses 99 percent less water without any pesticides and herbicides while planting 250 times more plants per acre. Additionally, John Deere’s AI-integrated See and Spray technology sprayers reduce fertilizer, fungicide, and herbicide by as much as 77 percent.

While conventional agriculture and fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide use are still very prevalent today, the sustainable agriculture movement has and will continue to grow.